Solo attorneys and small law firms are routinely victimized by perpetrators of attorney trust account scams, like the Fumiko Anderson scam. Why?

A few months ago, one of Law Firm Suites’ clients was sharing with us exciting news about a high dollar international collection case that fell in his lap through a website inquiry. He even showed us a copy of the high six-figure check that he was about to deposit into his attorney trust account.

This attorney’s guardian angel was clearly looking out for him that day, because he had no idea how close he came to being bilked out of hundreds of thousands of dollars in pervasive Internet IOLA scams being perpetrated on mostly solo attorneys and small law firms.

Despite a fair amount of press by bar associations and legal publications, it seems that there are still a large number of solo attorneys and small firm lawyers who have never heard about these scams.

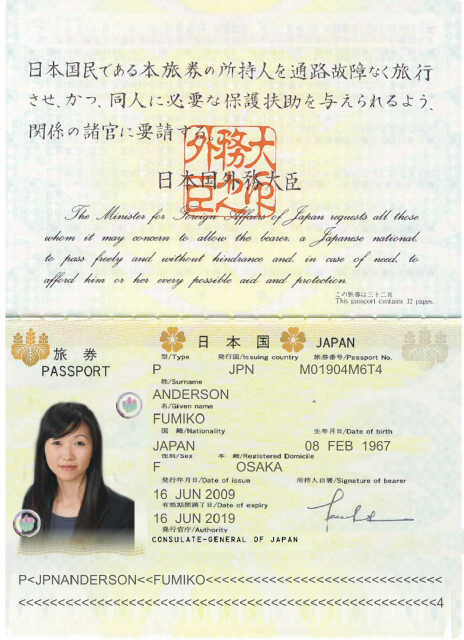

Fake client: Fumiko Anderson

Recently, our law firm received an email from a “Fumiko Anderson.” Ms. Anderson is the nom de plume of the latest, and ever evolving, Internet IOLA scam and is the latest example of the several trust account scam offers our firm sees every month.

In an effort to shed light on the latest iteration of this scam and help other solo lawyers and small firms avoid a costly financial hit, we engaged Ms. Anderson. Here’s how this scam works.

How the Fumiko Anderson Scam Works:

This scam is a variation of the classic bad check scam. Perpetrators target attorneys in seven steps.

1. Email solicitation coupled with the promise of easy money.

A solo or small firm attorney is initially solicited via email under the pretense of past due child support payments and unpaid alimony.

The major selling point is the amount of money in arrears ($677,050.00) and the client’s willingness to pay the attorney a big up front retainer and an exorbitant billable hour rate without hesitation.

2. The “client” sends somewhat legitimate looking documents.

After the attorney replies to the email, they are prompted to send an engagement agreement. The client promptly returns the engagement agreement together with legitimate appearing documents related to claim.

In the case of Fumiko Anderson, we received by overnight courier:

1. A signed copy of the engagement agreement;

3. A decree of divorce; and

4. A copy of Ms. Anderson’s passport.

Incidentally, our engagement agreement listed an hourly rate of $2,750.00, which was agreed to without question. This, in and of itself, should tip off the attorney that the client is fake.

3. The underlying dispute is quickly solved and a check is disbursed.

The attorney then receives an email from the client advising of very good news: the mere act of retaining counsel compelled the adverse party to make a settlement offer.

In this case, Fumiko advised us that her ex-husband, Bill Anderson, agreed to provide a one-time lump sum settlement satisfying the past due alimony and child support. Fortuitously, we were advised that Mr. Anderson would be sending a check representing the settlement proceeds directly to our firm and we should receive it in a few days.

Three to five days pass and the attorney receives a legitimate-looking cashier’s check from a real bank, usually by overnight courier from a first-world country.

In our case, we received a cashier’s check from Citibank by DHL from Canada.

The attorney then deposits the check into his or her attorney escrow account for eventual disbursement to the client. Easy money, right?

4. The client urgently requests for a distribution of funds.

The client then sends an email to the attorney stating that her needs have suddenly changed and that she requires a portion of the settlement proceeds immediately. The attorney is then instructed to disburse this amount by wire transfer to an offshore account, less the attorney’s fees, of course. In another variation of this scam, the client instructs the attorney that the balance should be kept in the attorney’s account as the retainer for future services.

The lure of a big retainer sitting an escrow account to be drawn down at the attorney’s full hourly rate is all-too-enticing for most counselors, who become very motivated to accommodate the client’s request despite their instinct that this may not be Kosher. The scammers know this and play off this

5. The bank clears a portion of the illegitimate funds and the attorney wires the money.

When the attorney calls his or her bank (or checks the IOLA bank account balance online) he or she will discover that a portion of the funds from the check will be available. Ironically, the money available will always be just a little more than the client’s requested disbursement amount.

Unbeknownst to the attorney, it is often bank policy to immediately make available a percentage funds represented by an out-of-state or international check even though the legitimacy of the check (or availability of funds from the originating bank) has not been verified.

6. The client threatens the attorney with a bar complaint to pressure him to release funds.

If the attorney advises the client that funds have not fully cleared and refuses to send the wire, the scammer will aggressively threaten the attorney with a complaint to the State Bar if they does not release the client’s funds.

Solo attorneys and small firms are particularly sensitive to these kinds of complaints (and scammers know it). After all, there is no easier way to lose your law license than running afoul of ethical regulations relating to the maintenance of client funds.

Often, the attorney succumbs to the pressure and releases the funds to the client.

7. The attorney wires the money before the bank discovers the check is a fake.

After the wire is sent, the bank notifies the attorney that the check is fraudulent.

The funds that were wired are not recoverable. The attorney is now legally responsible to the bank for the replacement of the money that was wired to the Fumiko Anderson’s of the world.

A Few Variations of the IOLA scam.

Frequently the “client” is a representative of a Chinese manufacturing company that allegedly seeks payment for goods shipped to a customer in America, typically a fake American company.

Sometimes the companies engaged in the dispute will have websites, phone numbers and will appear legitimate. The American defendant may have also been formed as a corporation in Delaware or Nevada.

The investor asked the real estate agent for a referral to an attorney that the broker trusts. The agent referred the investor to an attorney to whom the broker had previously referred business. The attorney was then asked to keep the investor’s purchase money in the attorney’s trust account so the investor could quickly close on a property once something suitable was found.

The attorney received a check from the investor and deposited it into his trust account. Shortly thereafter, the attorney received correspondence from the investor that he had an emergency of some sort at home, and required that the funds be returned immediately.

Because the investor was introduced to the attorney by the real estate broker, a key referral source that the attorney wanted to keep happy, the attorney let his guard down and wired the portion of the funds that the bank initially made available.

Of course, the check was a fake and the attorney was on the hook to the bank for several hundred thousand dollars.

In some cases, the scammer will use the relationship between the broker and the attorney (and the attorney’s desire to not jeopardize the business referral source) as additional leverage to convince the attorney to send the funds more expediently.

Why solo attorneys and small law firms are easy targets for IOLA check fraud scams.

Solo attorneys are conditioned not to ask questions when new clients fall in our lap.

For many of us, it’s not uncommon for a paying client to land in our lap. Inexplicably, sometimes the phone just rings or a client finds you through your website.

So, when we receive an unsolicited email that promises significant compensation for a relatively basic matter, why question your good fortune? For many of us, we see a few legitimate cases like this every year.

Solos and small law firms have little or no systematic financial controls.

At a bigger law firm, when an attorney needs client funds disbursed from IOLA, the attorney would first have to submit to a check request to accounting. The accounting department then verifies the availability of funds with the bank. Typically, an experienced legal accounting staffer would not permit funds to be transferred until all the funds from a check have cleared. Once funds are confirmed as available with the bank, only then will accounting send the check request to a partner or finance committee for final review, approval and signature.

This process can sometimes take days, increasing the likelihood that someone from the firm or the bank discovers the scam. By comparison, the solo attorney merely has to make one call to the bank and the funds are gone.

One of the perks of solo law practice is the lack of bureaucracy, but the downside is greater exposure to the risk of bad financial decisions.

Solos and small firms can be isolated from legal peers and may not be “in the loop” about industry developments like IOLA scams.

Finally, small firm attorneys can be easy targets because they are frequently “out of the loop” on industry developments. At bigger firms, by virtue of having so many attorneys and many layers of management and staff, attorneys are better equipped to stay on top of legal industry news like these IOLA scams.

For the self-employed small firm attorney, it’s hard enough to keep up with changes in the law, marketing their practice, writing briefs, prepping for trial and making court appearances (sometimes all at the same time). Industry developments are sometimes overlooked.

The solo attorney who is not active in his or her bar association, or does not otherwise have a network of attorneys through their office arrangement like you would find in shared law office space like Law firm Suites, may not get timely access to legal industry developments like these scams.

All of these factors combined make small firm attorneys and solos easy targets.

Consequences of being victimized by a trust account scam.

There are two very significant consequences for lawyers who become victims of the IOLA scam:

1. Disciplinary Liability

Distributing the “client’s funds” may result in your trust account being overdrawn. As you know, banks are required to automatically report to the Bar any attorney with an overdrawn trust account.

Even if the wire does not result in the account being overdrawn, that just means that you will have sent another client’s funds to the perpetrators; an act that you must report to disciplinary authorities or risk losing your license to practice.

Either result will trigger a disciplinary investigation and audit of your trust account records. It may also result in disciplinary action for this incident, and for any other deficiencies the auditors find in your trust account record keeping.

2. Financial loss may not be covered by your professional liability insurance.

Even though you were the victim of a fraud, your bank will likely demand the return of funds wired to the “client.” Because the amounts can be in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, you may not have the means to do so.

To add insult to injury, your malpractice insurer will not likely cover the loss.

In Bank of California, N.A. v. Opie, 663 F.2d 977,988 (9th Cir. 1981), the Ninth Circuit held the status of a person as a “professional” within a particular field does not mean that any activity by that person constitutes the performance of “professional services” subject to coverage under a malpractice policy. According to the court, “[t]o be covered, the liability must arise out of the special risks inherent in the practice of the profession.”

In the case of the IOLA scam, in many states, endorsing, depositing and disbursing checks does not constitute “special risks inherent in the practice of the profession.” See, for example, Fleet Nat’l Bank v. Wolsky, Civil Docket CV2004-05075 (Mass. Superior Ct. 2006).

Therefore, your malpractice insurance will not likely cover the loss, and you will be responsible for repayment.

________

IOLA scams play off the solo and small firm attorney’s need to keep a full pipeline of cases.

We believe that variations of this scam will continue to increase, especially as more and more young attorneys start solo practices as a result of not being able to find jobs.

The scams have consequences that go far beyond hurt pride. If you do not perform your due diligence, you could end up appearing before your Bar’s disciplinary committee, in civil litigation with your bank, or in bankruptcy court.

The easiest thing to do is to proceed with caution with every easy money case, and never wire money from your attorney escrow account without written acknowledgement from the bank that all funds from a check are clear and that there are will be no issues with the deposited check (or the funds it represents).